(A busy intersection at the entrance to Mae Sot, near Burma border.)

(Refugee housing…)

(A woman washes her daughters soiled clothes after an episiotomy.)

Squatting over a pit toilet in a concrete compound, I heard the first bombs going off. I thought to myself, here it is – life on the border of Thailand and Burma (Myanmar).

It was day one, hour one in the small town of Mae Sot that lies only a few kilometers from the border. My heart raced and my breathing slowed. I emerged from behind the wall of the hospital to study the faces of the Burmese refugee’s (who, sadly I share no language with) and to confirm or deny if this is in fact a dramatic happening. No one looked the least bit bothered by the booming that shook the very ground we stood on. Either this is commonplace in such a politically charged terrain or I’m over-reacting, I thought.

I hurried over to a Karen tribal man who I knew spoke some English and he calmly told me, “No worry. Person died. Shooting and firework,” he says, “funeral, you know?” Then he chuckles a little, knowing precisely what this Western woman was thinking…

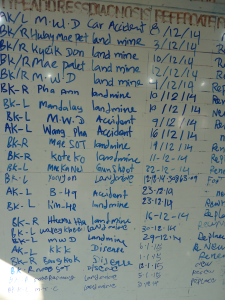

That was how I started my time at the Mae Tao Clinic at the border. Moments later, I was touring this hospital “compound” that exists to serve Burmese refugees because of its proximity to the border. Each day, trucks or motorbikes pull into the compound with patients found crossing the mountains. Land mines, protracted labor, and malaria being some of the most common ailments.

(Patients awaiting admission at Mae Tao Clinic.)

(The clinic affords two meals per patient, per day.)

(All services at the clinic are completely FREE for patients. On this day, an eye surgeon came to donate services and patients waited more than 12 hours to be seen over the course of 5 days.)

(Burma used to charge residents who stepped on landmines for “Destroying government property”.)

(Because of the high rate of landmine victims, they have a prosthetics lab onsite.)

(Me and Lweh Wah Say.)

Mae Tao Clinic receives more than 100 new patients each and every day. And let me just say, people do not come here unless they absolutely have to. It seems to serve more as a trauma unit on the border. Many people die on their way across the border and into the clinic. One morning on my way to the clinic I rode in a truck that moments earier had a dead woman wrapped in blankets in the bed. She had died of dehydration and the kind gentleman who was driving took it as his duty to bury her (nevermind that he was using his truck as a taxi). Since she was a refugee, she was not welcome to be cremated at the temple.

During my tour I passed through the Labor and Delivery room to find a 21 year old Karen woman who had been laboring for nearly 12 hours with very little dilation and her contractions were getting more and more sparse, rather than closer together. Next to her sat an 18 year old woman who’s contractions just began with such force she was screaming and thrashing backward and forward. The gentleman kind enough to show me around, Lweh Wah Say says to me, “can you do treatment to help?”

Then before I knew it, I had the young woman who had been laboring for hours, sitting between my legs, water broke, contractions began coming every 3 minutes and within the hour, she had delivered a healthy, 7.5 lb baby boy. This is her and her family…

And 4 hours later, there were 4 more women who delivered with the help of acupuncture and acupressure. By the end of my week there, I had attended more births than I can count and assisted in more than 25 labor and deliveries. Amazing experience. I feel so blessed to have been a part of this clinic and there is no doubt I will return.

(The laboring room…no cushions except for a plastic pillow. Typically two or more women in here at a time. This became my treatment room.)

(The delivery room. I caught this picture in a very special moment where no one was delivering!)

(This baby was a part of a set of twins, both born early and with congential lung and heart problems, yet to be diagnosed.)

(One-third of the labor and delivery ward consisting mostly of women in labor or with complications.)

(Because of the high volume of patients and the high risk deliveries, sometimes babies would have to lay for an hour or more before being handed to their families. When I had the time, I always went and snatched them up as it went against every cell in my body to hear them crying.)

(A little one, minutes old, waiting for mom…)

(The more fragile twin spent the night in an incubator.)

(The amazing women of Labor and Delivery.)

Because of the intense nature of this clinic, I was very selective of taking pictures. I chose not to take pictures of the women I treated who were in labor. In part this was because we could not speak the same language and I was more concerned with making them comfortable and assisting them rather than making them feel like a specimen. I wasn’t able to explain to them why I wanted to take their picture anyhow. Secondly, these were mostly women from the tribal areas and I was uncertain of their customs around photos in general. And lastly, some of these women were having the scariest moment of their entire lives. They were in a lot of pain (this clinic does not do epidurals) and were very vulnerable. I wanted to help them to feel empowered and supported. Therefore, the only photo I took of the individual women I treated was the 21 year old and her family. This was because they came up to thank me with a translator as they were moving to a different part of the clinic and I felt I could ask.